From its infancy as music for the urban elites to its heyday as the soundtrack for the liberation movement in Ghana, highlife music has remained the bedrock of West African popular culture. This is the story of a genre that has survived through generations and different trends to retain its unique identity amidst a host of contemporary influences

The earliest influence on the Ghanaian musical genre that has become known as highlife was rural palm-wine music, the guitar-dominated style of music that was played at venues where palm wine was sold. Over many generations, highlife has experimented and evolved, drawing from a combination of West African folk music, church hymns and Western styles like calypso, swing, jazz and soul. Today, the genre has given birth to incarnations like hiplife (highlife and hip-hop) and Azonto.

The earliest brass bands to play one of the original forms of highlife, known as ‘adaha’, emerged in the south of Ghana (then known as the Gold Coast) in the 1880s but it was not until 1914 that the first dance orchestras became famous. Most of these were military bands, formed by Ghanaian soldiers returning from the First World War, where they had been exposed to the musical styles of the Caribbean and Europe when they fought alongside foreign soldiers in the British colonial regiments.

Because the music was played to upper-class audiences in ballrooms, it was given the name ‘highlife‘, as in, high-class music. ‘Yaa Amponsah’ by the Kumasi Trio is the first known highlife song to be officially released. It was issued on the Zonophone label in London in 1928. Other international labels like EMI and Gallo Africa also released several highlife records up until the 1950s. Ghana’s first indigenous music production company, Ambassador Records Manufacturing Company, was set up in Kumasi at the end of the 1950s.

Highlife was the first true Pan-Africanist music

A new era

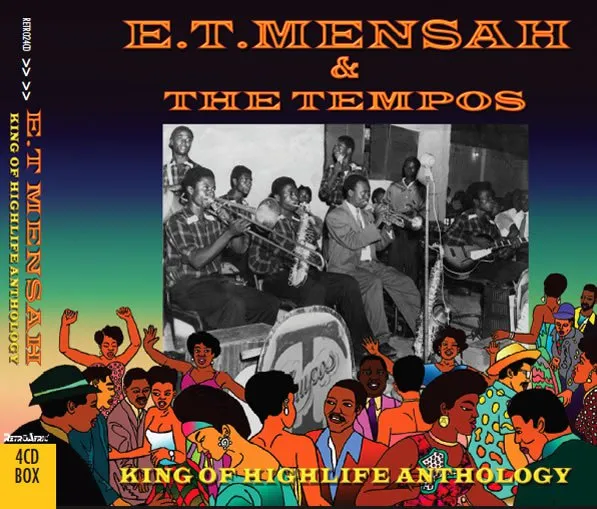

After the Second World War, jazz-influenced dance bands replaced the orchestras and transformed the sound of highlife, fusing it with other genres like soul, calypso, rumba and swing. The Tempos was the most successful of the pioneer professional highlife bands in the then Gold Coast. Formed in 1946 by European soldiers serving in the country, the band passed into African hands, when the original members left for other stations. Trumpeter and saxophonist Emmanuel Tetteh Mensah joined the group in 1947 and it officially became E T Mensah and his Tempos Band in 1950.

Mensah, who became ‘The King of Highlife’ is credited with transforming highlife from a little-known style of music in Ghana to a dominant musical force in West Africa and beyond. His fusion of swing, calypso and Afro-Cuban music exported highlife music to Nigerian cities like Lagos, Ibadan, Benin City and Warri. The influence of highlife spread from Ghana and Nigeria to Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone and as far afield as the then Congo and Kenya in the 1960s and 1970s.

Advertisement

The harmonies of highlife was enriched with the addition of a rhythm section consisting of bongos, conga, drums, guitar, bass and maracas. Mensah provided a bridge between highlife and Nigerian Afrobeat by recording and performing with Fela Kuti and Dr Victor Olaiya, who was known as ‘The Evil Genius of Highlife’.

Because the music was played to upper-class audiences in ballrooms, it was given the name ‘highlife’

The rise of concert parties

One of the features of highlife performances that became popular from the 1950s onwards was the so-called ‘concert parties’. Improvised theatre revolving around the realities of Ghanaian social life was performed by comedians, actors, dancers and singers. The combination of highlife and theatre created one of the most significant chapters in the history of the genre.

Celebrated Ghanaian musician E K Nyame transformed concert parties by introducing original highlife music in local languages to replace American and European songs while his troupe of actors, the Akan Trio, would dramatise the proverbs and other folklore mentioned in the lyrics of the songs. This established a new trend in concert parties and completely revolutionised this performance format in an era of strong anti-colonial and pro-African passions.

Advertisement

Inevitably, highlife gained a strong association with the liberation movement in Ghana and Kwame Nkrumah proclaimed it Ghana’s national dance music. After independence in 1957, Nkrumah, as prime minister and later president, would often be accompanied by highlife musicians like Nyame on his tours of African countries to promote his Pan-Africanist movement. Many Ghanaian musicians switched from English lyrics to indigenous languages like Twi and Akan, in line with Nkrumah’s ‘African Personality’, an ideology defined as ‘the creative expression of the African genius, the common reality behind the diversities and complexities of African cultures’.

Nkrumah urged highlife artists to make music that was more Ghanaian in character and to eliminate any foreign influences from their sound. If the Ghanaian leader had had his way, even the name of the music would have changed from highlife to the Akan word ‘osibi’, which was one of the original names of this musical style. To Nkrumah, true independence was as much about his people’s cultural awakening as it was about their political and economic liberation.

“King of Highlife Anthology” 4 CD box cover

The sound of politics

Highlife musicians recorded praise songs for the Ghanaian leader, for example ‘Nkrumah Highlife’ by the Tempos, ‘Kwame Nkrumah’ by Kwaa Mensah and ‘Nkrumah ko Liberia’ (Nkrumah is going to Liberia) by the Fanti Stars. However, when discontentment set in during the early years of Nkrumah’s rule after independence, highlife songs again best captured the political feelings in Ghana. The African Brothers used fables of animal characters to criticise the tyranny and oppression that eventually led to the overthrow of Nkrumah’s government in a military coup in 1966.

The decline of highlife began in the 1970s as the dominance of American and European pop music began to set in. A few Ghanaian bands, like the Ashanti Brothers and City Boys, survived by playing a hybrid of highlife and Western pop, soul and reggae. Meanwhile, in Nigeria, highlife legends like Prince Nico Mbarga and his band, Rocafill Jazz, were being produced. They recorded one of Africa’s best-known songs, ‘Sweet Mother’. Other famous performers included the likes of Sonny Okosun and Victor Uwaifo.

Death by disco

As was the case in many parts of Africa in the 1980s, the emergence of disco units, with their low operational costs, sounded the death knell for many highlife bands in Ghana. Moreover, the country’s music industry had taken a massive hit from the economic slump of the 1970s, resulting in many musicians moving abroad while those who remained behind switched to the fast-rising gospel sound.

Gospel-highlife grew in popularity, boosted by churches adopting the concept of concert parties, that old format of music combined with theatre. However, music sales were greatly hampered by the piracy of cassettes, the main format of music distribution at the time.

The combination of highlife and theatre created one of the most significant chapters in the history of the genre.

The sounds of revival

It was not until the beginning of the 1990s that a revival of highlife occurred, albeit in a new format. Known as hiplife, this was a hybrid of highlife and hip-hop started by Ghanaian-American rapper Reggie Rockstone. This sound resonated with Ghanaian youth, because while the music borrowed from American-style rap, it still contained a distinct identity. This identity came from the fact that the hybrid sound drew from original highlife music and featured lyrics in local languages, like Twi, in Rockstone’s case.

The popularity of reggae led to the development of yet another genre, known as Raglife, which is a combination of reggae and highlife.

Looking back with pride

As these new formats have emerged, there is renewed interest in the classic highlife recordings of the last 70 years, some of which have been remastered and rereleased. For example, E T Mensah’s collection was digitally transferred from shellac discs at the British Library’s Sound Archive and was released as a 4 CD boxset in 2015. http://www.retroafric.com/

In Nigeria, contemporary artists like 2Face Idibia and Mr Flavor have kept the heritage of highlife alive by recording remixes and cover versions of classic songs.

Highlife was the first true Pan-Africanist music and its survival in different contemporary formats today is testament to its original ability and intention: to embrace and adapt to diverse rhythms without losing the core of its identity.

SOURCES: This is Africa